|

THE

RED SEA

HOME -

A-Z INDEX

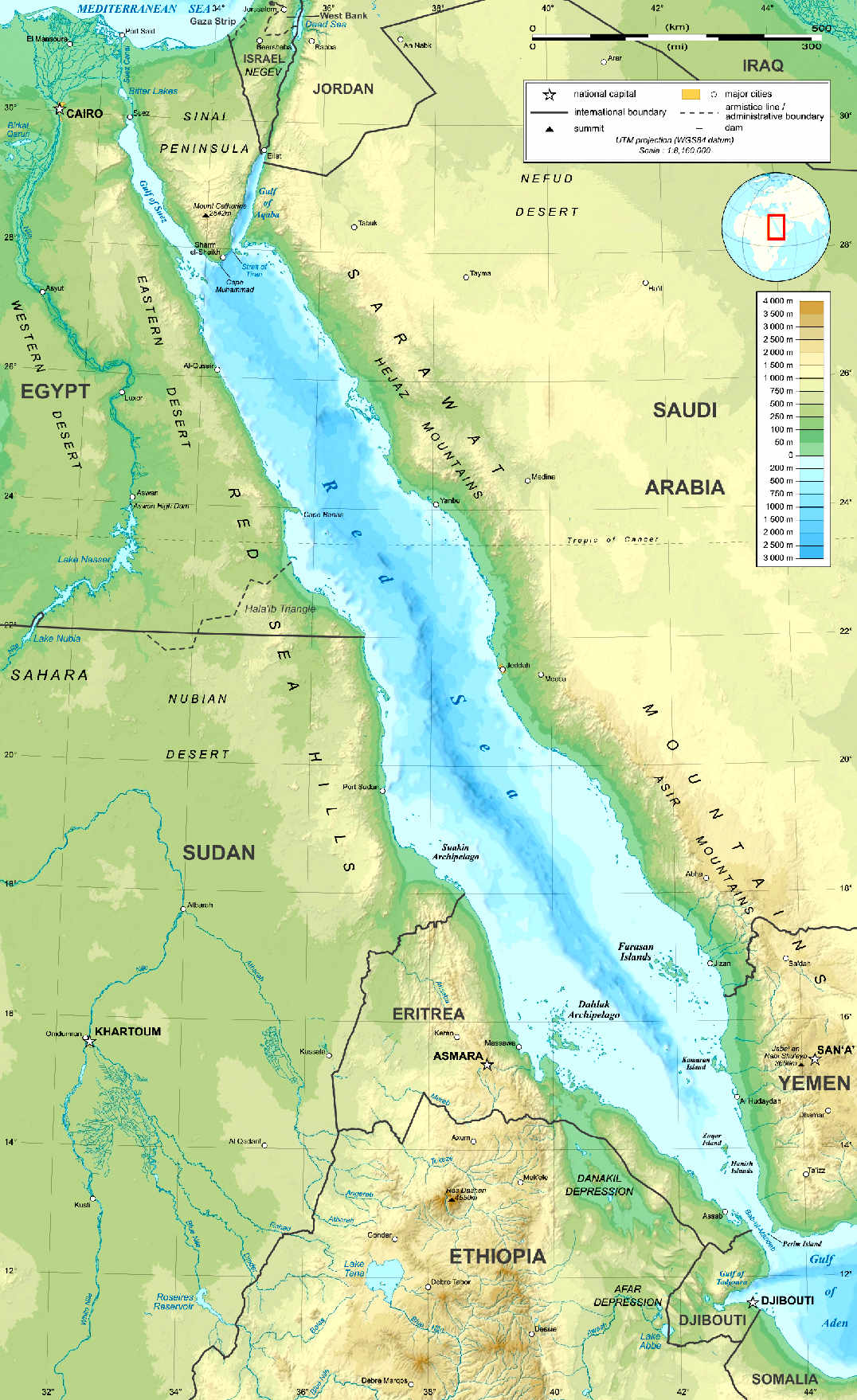

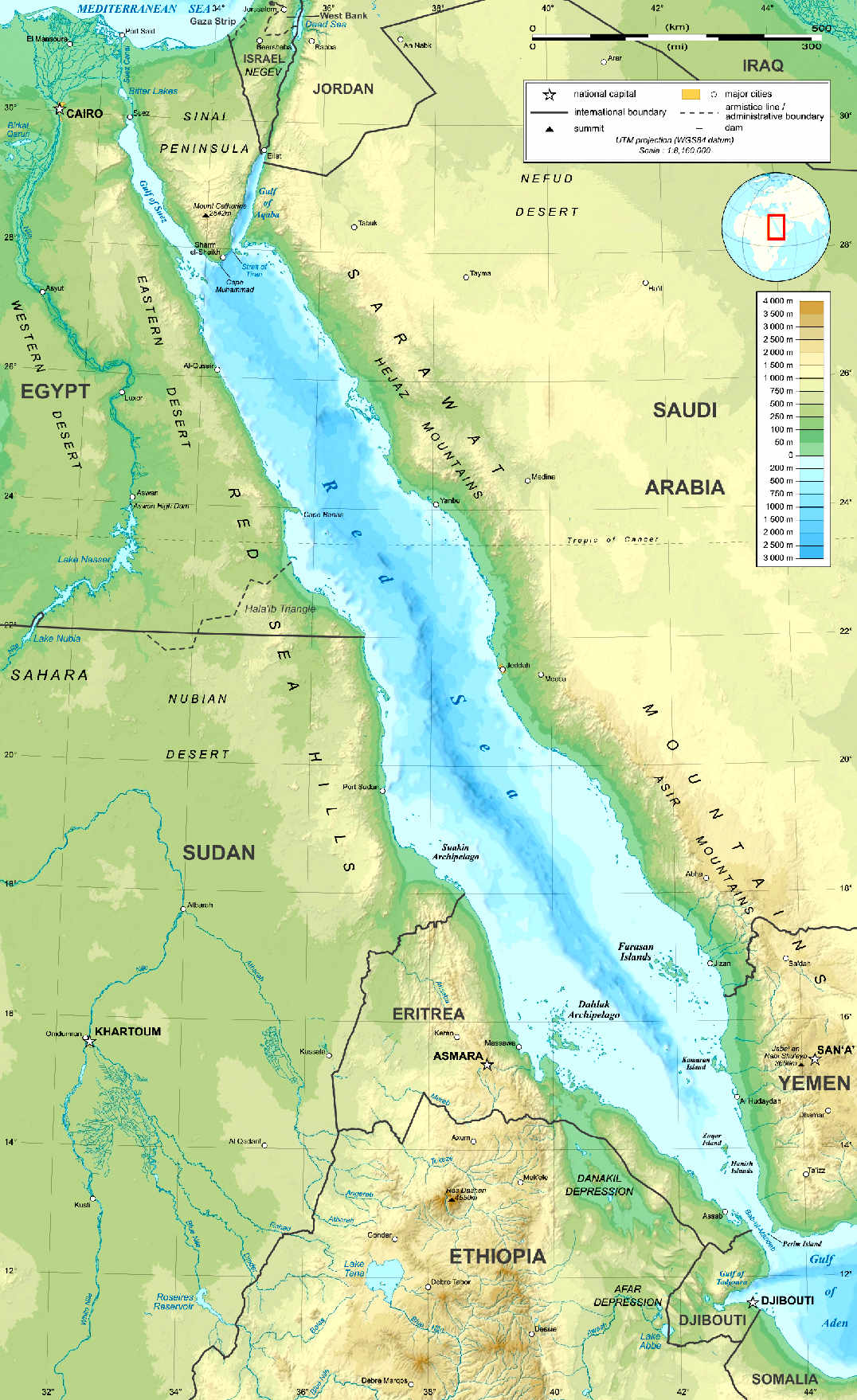

The Red Sea is a seawater inlet of the

Indian

Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and the Gulf of Suez (leading to the

Suez

Canal). It is underlain by the Red Sea Rift, which is part of the

Great Rift

Valley.

The Red Sea has a surface area of roughly 438,000 km2 (169,000 sq mi), is about 2,250 km (1,400 mi) long, and — at its widest point — 355 km (221 mi) wide. It has an average depth of 490 m (1,610 ft), and in the central Suakin Trough it reaches its maximum depth of 3,040 m (9,970 ft).

Approximately 40% of the Red Sea is quite shallow (less than 100 m (330 ft) deep), and about 25% is less than 50 m (164 ft)

deep. The extensive shallow shelves are noted for their marine life and corals. More than 1,000 invertebrate species and 200 types of soft and hard coral live in the sea. The Red Sea is the world's northernmost tropical sea, and has been designated a Global 200 ecoregion.

OCEAN

AWARENESS CAMPAIGN - As

part of the Cleaner Ocean Foundation's ocean

literacy campaigns, the not for profit is developing the Elizabeth

Swann, a solar and hydrogen powered craft, to demonstrate

clean blue water and river cruises are technologically closer

than you might think. Hence, Mediterranean, Red Sea, and Nile

river cruises.

OCEANOGRAPHY

The Red Sea is between arid land, desert and semi-desert. Reef systems are better developed along the Red Sea mainly because of its greater depths and an efficient water circulation pattern. The Red Sea water mass-exchanges its water with the

Arabian

Sea, Indian Ocean via the

Gulf of

Aden. These physical factors reduce the effect of high salinity caused by evaporation in the north and relatively hot water in the south.

The climate of the Red Sea is the result of two monsoon seasons: a northeasterly monsoon and a southwesterly monsoon. Monsoon winds occur because of differential heating between the land and the sea. Very high surface temperatures and high salinities make this one of the warmest and saltiest bodies of seawater in the world. The average surface

water temperature of the Red Sea during the summer is about 26 °C (79 °F) in the north and 30 °C (86 °F) in the south, with only about 2 °C (3.6 °F) variation during the winter months. The overall average

water temperature is 22 °C (72 °F). Temperature and visibility remain good to around 200 m (660 ft). The sea is known for its strong winds and unpredictable local currents.

The rainfall over the Red Sea and its coasts is extremely low, averaging 60 mm (2.36 in) per year. The rain is mostly short showers, often with thunderstorms and occasionally with dust storms. The scarcity of rainfall and no major source of fresh water to the Red Sea result in excess evaporation as high as 2,050 mm (81 in) per year and high salinity with minimal seasonal variation. An underwater expedition to the Red Sea offshore from Sudan and Eritrea found surface

water temperatures 28 °C (82 °F) in winter and up to 34 °C (93 °F) in the summer, but despite that

extreme heat, the coral was healthy with much fish life with very little sign of coral bleaching, with only 9% infected by Thalassomonas loyana, the 'white plague' agent. Favia favus

coral there harbours a virus, BA3, which kills T. loyana. Scientists are investigating the unique properties of these coral and their commensal

algae to see if they can be used to salvage bleached coral elsewhere.

ECOSYSTEM

The Red Sea is a rich and diverse ecosystem. More than 1200 species of fish have been recorded in the Red Sea, and around 10% of these are found nowhere else. This also includes 42 species of deepwater

fish.

The rich diversity is in part due to the 2,000 km (1,240 mi) of coral reef extending along its coastline; these fringing reefs are 5000–7000 years old and are largely formed of stony acropora and porites corals. The reefs form platforms and sometimes lagoons along the coast and occasional other features such as cylinders (such as the

Blue Hole (Red Sea) at Dahab). These coastal reefs are also visited by pelagic species of Red Sea fish, including some of the 44 species of

sharks. Other marine habitats include sea grass beds, salt pans, mangrove and salt marsh.

It contains 175 species of nudibranch, many of which are only found in the Red Sea.

The Red Sea also contains many offshore reefs including several true atolls. Many of the unusual offshore reef formations defy classic (i.e., Darwinian) coral reef classification schemes, and are generally attributed to the high levels of tectonic activity that characterize the area.

The special biodiversity of the area is recognized by the

Egyptian

government, who set up the Ras Mohammed National Park in 1983. The rules and regulations governing this area protect local marine life, which has become a major draw for diving enthusiasts.

Divers and snorkellers should be aware that although most Red Sea species are innocuous, a few are hazardous to

humans.

The U.N. is working to mitigate the threat from the FSO Safer, a derelict

oil

tanker off the coast of Yemen that could possibly cause an enormous ecological disaster in the Red Sea.

The brine pools Red Sea have been extensive studied in terms of their microbial life. The Red Sea brine pool microbiology is characterized by its diversity and adaptation to extreme environments.

TOURISM

The sea is known for its recreational diving sites, such as Ras Mohammed, SS Thistlegorm

(shipwreck), Elphinstone Reef, The Brothers, Daedalus Reef, St. John's Reef, Rocky Island in

Egypt and less known sites in Sudan such as Sanganeb, Abington, Angarosh and Shaab Rumi.

The Red Sea became a popular destination for diving after the expeditions of Hans Hass in the 1950s, and later by Jacques-Yves Cousteau. Popular tourist resorts include El Gouna, Hurghada, Safaga, Marsa Alam, on the west shore of the Red Sea, and

Sharm-el-Sheikh, Dahab, and Taba on the

Egyptian side of Sinaï, as well as Aqaba in Jordan and Eilat in Israel in an area known as the Red Sea Riviera.

The popular tourist beach of Sharm el-Sheikh was closed to all swimming in December 2010 due to several serious shark attacks, including a fatality. As of December 2010, scientists are investigating the attacks and have identified, but not verified, several possible causes including

over-fishing which causes large sharks to hunt closer to shore, tourist boat operators who chum offshore for shark-photo opportunities, and reports of ships throwing dead livestock overboard. The sea's narrowness, significant depth, and sharp drop-offs, all combine to form a geography where large deep-water

sharks can roam in hundreds of meters of water, yet be within a hundred meters of swimming areas. The Red Sea Project is building highest quality accommodation and a wide range of facilities on the coast line in

Saudi

Arabia. This will allow people to visit the coastline of the Red Sea by the end of 2022 but will be fully finished by 2030.

RED

SEA CRISIS 2023-2024 - THE GUARDIAN 13 JANUARY

A prolonged conflict in the Red Sea and escalating tensions across the Middle East risk having devastating effects on the global economy,

re-igniting inflation and disrupting energy supplies, some of the world’s leading economists warn this weekend.

Before a statement expected on Monday by Rishi Sunak in the

House of Commons about UK and US airstrikes on Houthi sites in Yemen, economists at the

World Bank say the crisis now threatens to feed through into higher interest rates, lower growth, persistent inflation and greater geopolitical uncertainty.

After a second night of strikes against the Iranian-backed rebels in Yemen, President Joe

Joe

Biden said that the US had sent a private message to Tehran that “we’re confident we’re well prepared”. Speaking to reporters on the White House lawn on Saturday, on his way to Camp David, Biden declined to go into further detail.

But there is now growing concern in government circles in London and Washington that as Sunak and Biden fight for re-election, events in the Middle East could dash what had looked like improved prospects for economic recovery and therefore their chances at the ballot box.

While the airstrikes against Houthi targets in Yemen have broad cross-party support at Westminster, Sunak will face questions from anxious MPs about a prolonged conflict and the longer-term plan for Middle East peace. Some leftwing Labour MPs are expected to put

Keir Starmer under pressure over why he backed the military strikes having said that he would only support such action after parliament had voted in favour of it.

Biden also faced pushback from progressives in his own party, already deeply opposed to US military support for Israeli action in Gaza. California congressman Ro Khanna said: “The president needs to come to Congress before launching a strike against the Houthis in Yemen and involving us in another Middle East conflict.”

In its latest report on global economic prospects, the World Bank says the Middle East crisis, with the war in

Ukraine, has created real dangers. “Conflict escalation could lead to surging energy prices, with broader implications for global activity and inflation,” it says.

“Other risks include financial stress related to real interest rates, persistent inflation, weaker than expected growth in China, further trade fragmentation and climate change-related disasters.”

It adds: “Recent attacks on commercial vessels transiting the Red Sea have already started to disrupt key shipping routes, eroding slack in supply networks and increasing the likelihood of inflationary bottlenecks. In a setting of escalating conflicts,

energy supplies could also be substantially disrupted, leading to a spike in

energy prices. This would have significant spillovers to other commodity prices and heighten geopolitical and economic uncertainty, which in turn could dampen investment and lead to a further weakening of growth.”

John Llewellyn, former chief economist of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), said: “This has escalated to become a serious problem.” He put the probability of serious disruptions to world trade at 30%, up from 10% a week ago:

“There is a horrible and inevitable progression that could see the situation in the Red Sea spread to the strait of Hormuz and the wider Middle East.”

An economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, Ben Zaranko, told

the Observer the crisis underlined the perils of the chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, using limited fiscal headroom to promise tax cuts. “If we have learned anything over the last few years it is that bad shocks can and do come along,” Zaranko said. “Spending every single penny of ‘headroom’ on tax cuts leaves him no room for manoeuvre if a nasty shock comes along and the outlook deteriorates.”

The conflict in the Middle East widened on Thursday when dozens of British and US strikes hit Houthi sites in Yemen. The strikes were in retaliation for attacks on vessels passing through the Red Sea, which have paralysed

shipping in one of the world’s most important maritime channels.

The Houthis say they are targeting only Israel-affiliated vessels, in an effort to support Palestinians in Gaza, but many of their targets had no known links to

Israel. They have also fired missiles at Israel’s territory.

A US strike on a radar site in Yemen on Friday night prompted Houthi threats of a “strong and effective response” to international attacks, and fuelled fears of regional escalation in a conflict already playing out across multiple borders.

Houthi spokesperson Mohammed Abdulsalam said the strikes had had no significant impact on the Houthis’ ability to prevent vessels from passing through the Red Sea and the Arabian Sea.

The top UN official for Yemen, special envoy Hans Grundberg, warned of “serious concerns” about stability and the fragile peace efforts in Yemen, which has endured years of civil war.

The Houthis are just one of several Iran-aligned groups across the region, including in Syria, Iraq and Lebanon, which are attacking targets either inside Israel, or which they say are linked to Israel. Hezbollah in Lebanon represents perhaps the most severe threat.

Farea Al-Muslimi, from the Chatham House Middle East programme, said: “The Houthis are far more savvy, prepared and well-equipped than many western commentators realise. Their recklessness, and willingness to escalate in the face of a challenge, is always underrated.”

William Bain, the British Chamber of Commerce’s trade expert, said: “About 500,000 containers were going through the Suez canal in November and that had dropped 60% to 200,000 in December.”

Ships are taking different routes, but that has raised costs, with a container that cost $1,500 in November rising to $4,000 in December.

“If things get worse, it only adds to the disruption, and the cost of containers will go up and global trade will fall further,” he said.

Economists, many of them arriving in Davos this week for the annual

World Economic

Forum, have become increasingly worried that many of the world’s major economies may now suffer a recession this year. They fear that central banks will make only modest cuts to borrowing costs, adding to the cost of living crisis faced by millions of households.

The prospect of higher oil prices could convince central banks to hold firm and maintain high interest rates for a longer period than currently expected.

Liam Byrne, chair of the Commons business and trade select committee, said: “There’s now a real risk that a Red Sea battle will push up prices, just as inflation was beginning to fall. The World Bank is already warning that global supply chains are once more in peril … not least because this new struggle in Suez comes as drought is cutting trade through the

Panama

canal. Two of the world’s five keys to trade are now in real jeopardy.”

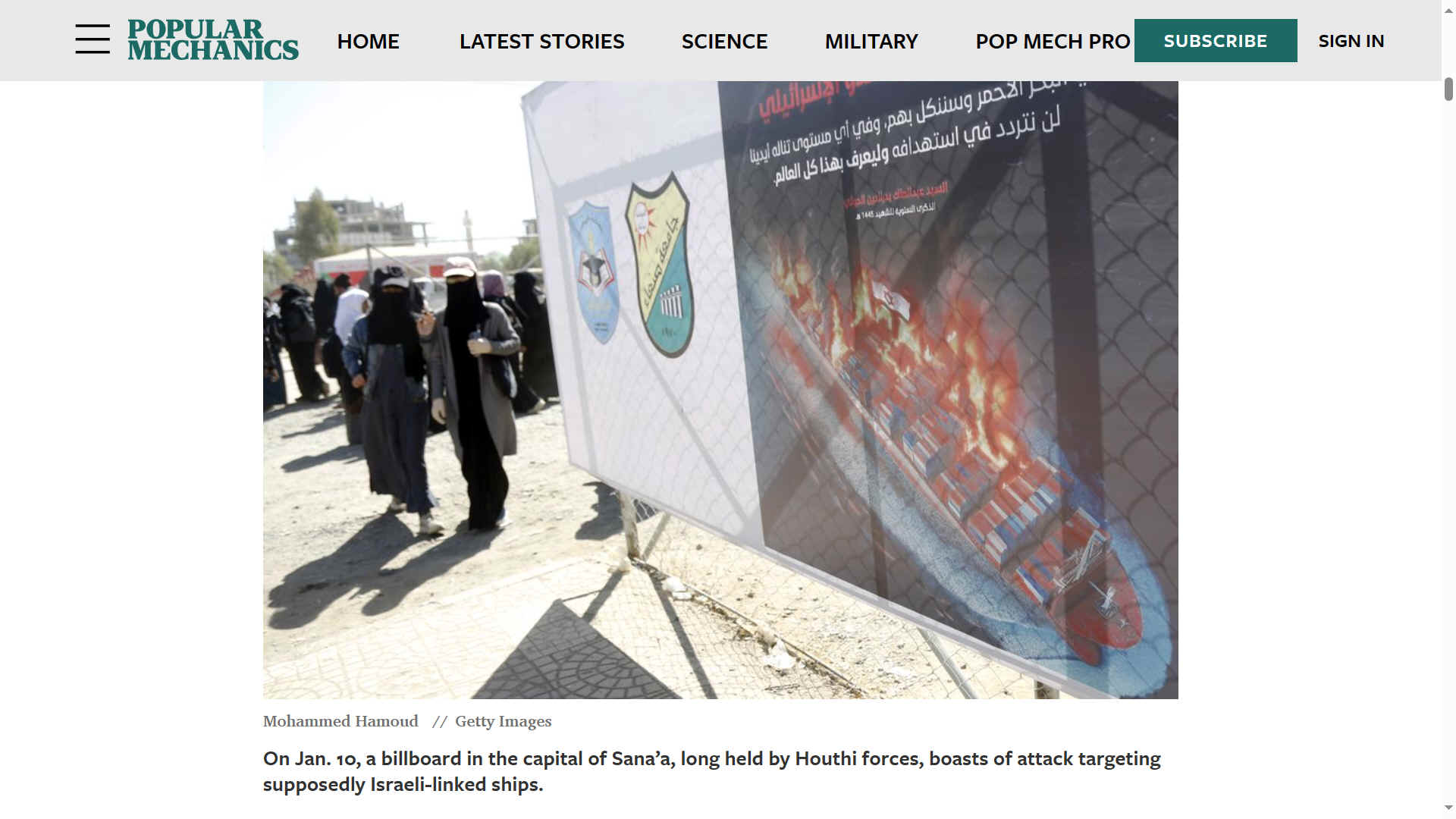

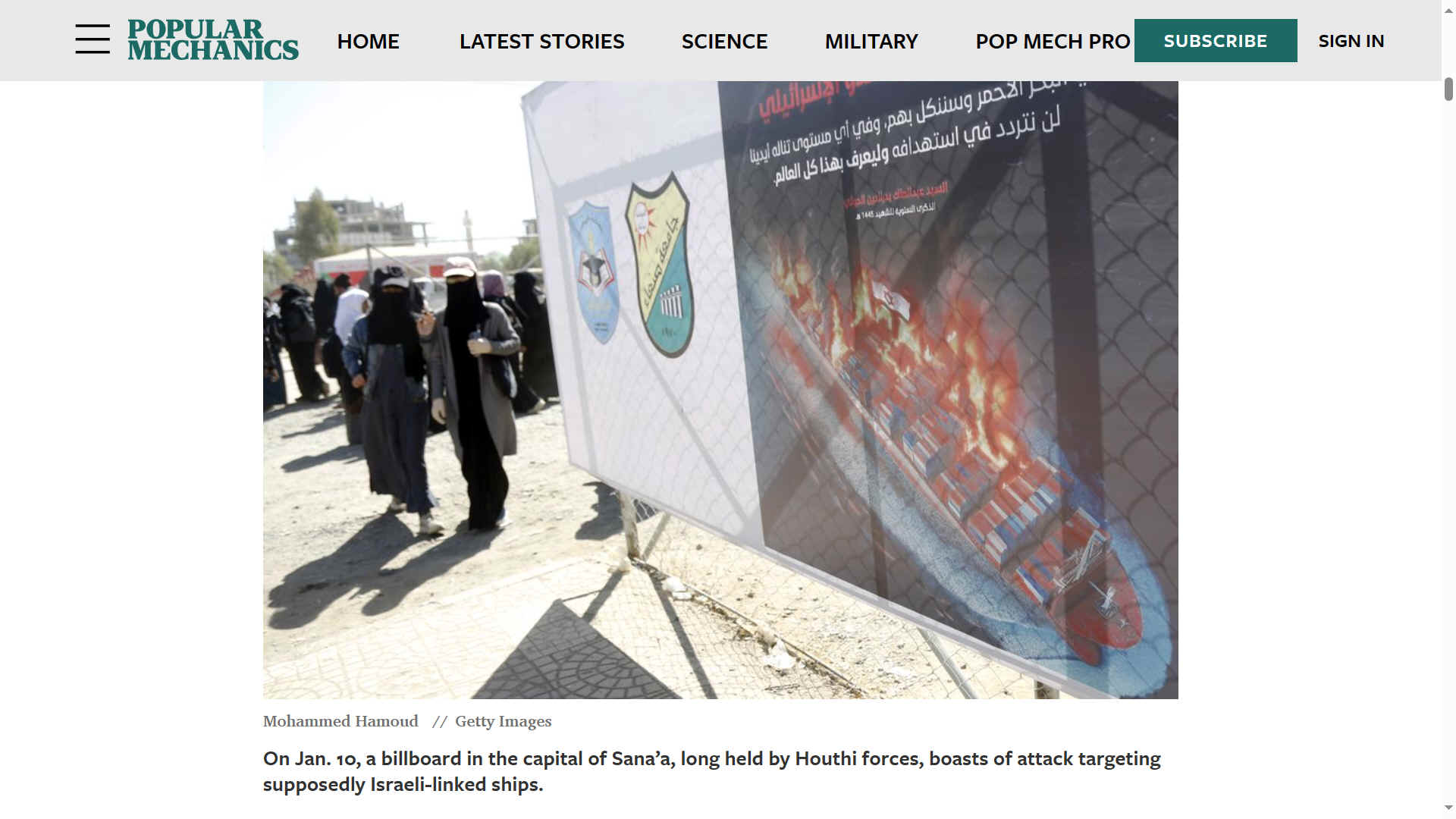

POPULAR

MECHANICS JANUARY 12 2024 - A SHORT HISTORY OF ANTI-SHIP BALLISTIC MISSILE ATTACKS

Over 100 Tomahawk cruise missiles and precision-guided bombs rained down on the military assets of Houthi militants in Yemen on Friday

morning - a substantial retaliation by the U.S. and British military following over two months of continual Houthi drone and missile attacks on civilian and military shipping in the Red Sea.

The Houthis, who control most of western Yemen, had declared open season on supposedly Israel-linked shipping and escorting warships in the Red Sea in response to Israel’s war with Hamas in Gaza. Those waters are undeniably economically important, as 30 percent of the planet’s container shipping traverses through them.

Of the 27 Houthi attacks targeting Red Sea shipping since October, none managed to hit U.S. or allied warships. But several did strike civilian ships — so far without causing any deaths or sinkings.

The U.S. and British strike Thursday evening hit 60 targets at 16 different locations in

Yemen, including coastal radars and command and control facilities used to coordinate attacks, as well as missile and drone storage depots, launchers, and production facilities. The Houthis reported that five of their militants were killed in the attacks and vowed retaliation.

U.S. warships and the Ohio-class cruise missile submarine Florida contributed to the strike, as did 15 F/A-18 Super Hornet and EA-18G Growler jets from the U.S. Navy’s Carrier Air Wing 3. Four Typhoon FGR.4 fighter-bombers of the United Kingdom’s Royal Air Force (RAF) based in Cyprus also contributed, and the governments of

Australia, Bahrain,

Canada, and the Netherlands are described as “supporting” the strike.

JANUARY 9; DRONE AND MISSILE WAR ON THE RED SEA

Thursday’s bombardment followed a large-scale night attack targeting U.S. and British warships on the Red Sea on Tuesday. The Houthis hurled 18 kamikaze drones laden with explosives, two anti-ship cruise missiles (skimming low over the surface of the ocean), and an anti-ship ballistic missile (approaching from above at supersonic speeds) at the vessels patrolling the Red Sea under the auspice of an operation known as ‘Prosperity Guardian.’

However, the concerted attack effort achieved little more than a

multi-million dollar fireworks display.

The Royal

Navy’s Type 45 destroyer HMS Diamond accounted for seven drones, using her Sea Viper system (the British/French Aster 15 and 30 missile) and close defense

guns - indicating that some of the drones did get close. F/A-18 Super Hornet fighter jets from the carrier Dwight D. Eisenhower shot down additional incoming munitions.

Polishing off the remainder were U.S. Navy Arleigh Burke-class destroyers Gravely, Laboon, and Mason, bristling with a half-dozen different types of surface-to-air missiles guided by fire control radars networked together via their shared Aegis Combat Systems.

THE U.S. NAVY'S GROWING TALLY OF BALLISTIC MISSILE KILLS

Compared to the surface-skimming cruise missiles dominating anti-ship warfare since the 1960s, ballistic missiles leap towards space in a long arc (in some cases exiting the atmosphere) and plunge back downwards at supersonic speeds.

As detailed in this Popular Mechanics feature, anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs) able to home in on moving ships were rare and exotic weapons that never before used in combat before a missed Houthi missile attack last November. But more would soon fly over the Red Sea.

Indeed, the ASBM downed on January 9 was actually the seventh shot down by U.S. warships in the last few weeks, going by the count of the Pentagon’s Central Command.

Notably, on December 30, 2023 at 8:30 PM, the USS Gravely reportedly shot down two ASBMs while coming to the aid of the Maersk Hangzhou after the latter was struck by a missile of undetermined type.

The day before (between 5:45 and 6:10 PM) her sistership, the Mason, downed another ASBM, along with a drone heading towards a concentration of 18 commercial vessels.

Prior to that, on December 26, the destroyer Laboon (with assistance from Eisenhower’s F/A-18 fighters) downed three Houthi ASBMs, as well as twelve drones and two land-attack cruise missiles. Presumably, the latter were headed towards Israel, which has shot down Houthi missiles using its Arrow III

air defense system and F-35 Lightning stealth jets.

Unless an earlier ASBM intercept went unreported by Central Command, Laboon was the first ship to ever shoot down an anti-ship ballistic missile in combat.

There’s not much information on which means were used for the U.S. Navy air defense kills, though it’s known that Mason used SM-2 missiles to down Houthi drones and land-attack cruise missiles bound for Israel in October. It’s still unknown whether the destroyers made first combat use of SM-3 and SM-6 missiles, which were specifically designed for ballistic missile defense, to defeat the Houthi attacks.

BALLISTIC MISSILE HITS AND MISSES ON RED SAE SHIPPING

For every Houthi ASBM shot down, another flat-out missed -

like one that plummeted into the Gulf of Aden at 2 a.m. on Thursday within sight of commercial shipping. Before that, two Houthi-launched ASBMs splashed into the Red Sea within sight of several commercial vessels on January 2, two were launched on December 23, and one (targeting Maersk Gilbralter north of Bab-el-Mandeb strait) was launched on December 14.

On December 3, an ASBM that launched at 9:15 AM and was targeting the Unity Explorer “impacted in vicinity” (which sounds like a near miss). However, from 12:35 to 4:30 PM, Unity Explorer and bulk carriers Number 9 and Sophie II were all subsequently hit by missiles of unspecified type. Fortunately, all took only minor damage.

On one occasion, a Houthi ASBM was confirmed to have struck a

ship - on Dec. 15, container ship Palatium 3 was struck on its port side at 10:40 AM by one of two ASBMs launched, knocking a shipping container overboard and causing a fire that was contained by the crew.

Later, the chemical/oil tanker Swan Atlantic

- loaded with vegetable oils - was attacked by both a drone and ASBM. One of the two hit, damaging the vessel’s water tank and causing a small

fire.

Several other reports of missile hits don’t make it clear whether they involved cruise or ballistic missiles. But the unifying factor between all of these strikes is that none resulted in loss of lives or ships.

The underwhelming outcomes aren’t that surprising: during the 1980s-era “Tanker War” between Iran and Iraq, large commercial ships struck by cruise missiles proved remarkably durable. This is largely thanks to their sheer bulk and small crews, as compared to slender warships densely packed with hundreds of crew and explosive missiles, shells and fuel.

Bear in mind that the navigation, communication and guidance technology necessary to make ballistic attacks somewhat practical against ships at sea have only recently evolved. As a result, these weapons remains very challenging to employ, as the moving vessel must fall within the narrow field of view of the missile’s seeker once it begins its terminal plunge.

Still, China and Iran have built up ASBM inventories because these land-based weapons can safely threaten U.S. warships from a distance, and potentially from an angle and speed their defenses might struggle against.

The Houthis claim to field a half-dozen different types of ASBMs

- most apparently derived from similar Iranian weapons, but with substitutions for local production. These most recently include the 10-meter-long Asef missile and slenderer, 6-meter-long Falaq-1 missiles, with claimed ranges of 250- and 85miles respectively. Both were seemingly derived from the Iranian Khalij Fars ASBM.

The Houthis also developed the Moheet ASBM by converting old Soviet S-75 anti-air missiles, a Tankil missile based on the Iranian Ra’ad-500 with a claimed range of 310 miles, and two other short-range ASBMs. However, whether all of these are in use and operational is unclear.

Some, however, insist that the Houthi attacks didn’t actually involve true anti-ship ballistic missiles, but rather ordinary land-attack ones. A military source told Naval News that the Houthis first immobilize a targeted civilian ship via threats over the

radio, then obtain the immobile vessel’s geographic coordinates by drone for subsequent targeting by a short-range land-attack ballistic missiles, or SRBM. These usually miss anyway, due to ships drifting and SRBMs not being very accurate.

This could explain the low accuracy of Houthi ballistic strikes, but not apparent attempts to target these weapons at moving U.S. warships. Perhaps both genuine ASBMs and ordinary ballistic missiles were used.

ANTI-SHIP BALLISTIC MISSILES: NOT AS SCARY AS THOUGHT?

The growing ASBM threat had been on the U.S. Navy’s radar, spurring the development of capable ballistic missile defense weapons like the SM-3 and SM-6 missiles. It also likely spurred on continual upgrades to the ever-evolving Aegis Combat System, which networks together U.S. warships enabling cooperative engagements and rapid, coordinated responses to incoming threats.

Notably, ASBMs are in no way stealthy weapons - their high-altitude trajectory and speed make them very indiscrete to radar and infrared sensors, and their prominent launch flash may also be detected by infrared-sensors on the same SEWS infrared surveillance satellites used to warn of nuclear missile launches.

The Houthi’s Red Sea campaign has inadvertently created conditions for operational testing of U.S. Navy missile

defenses - and overall, this ‘battle laboratory’ suggest those defenses work well against Houthi ballistic missiles.

On the flipside, Houthi ballistic missiles have proven capable of hitting their targets, and U.S. warships have not always been close enough to shoot down missiles streaking towards civilian ships. So, the threat can’t be blithely dismissed.

It’s also important to not over-extrapolate from the performance of Houthi missiles in the Red Sea to other

contexts - particularly China and the Pacific

Ocean.

On the one hand, the short distances (dozens of miles) and confined geography of the Red Sea make it unusually easy for the Houthis to acquire targets, despite their limited maritime surveillance capability, using coastal radars and (perhaps) intel from the Iranian surveillance ship Behshad.

On the other hand, the shorter-range Houthi ASBMs are easier targets due to having slower peak

velocity - likely around Mach 3 or 4 - than Chinese DF-21D ASBMs designed to traverse up to 900 miles at Mach 10.

A wealthier adversary could have much better surveillance capabilities, the ability to provide course-corrections for missiles midflight, and enough launchers to fire many more munitions simultaneously in an attempt to overwhelm the air defenses.

The Houthi Red Sea missile war demonstrates that ballistic missiles have arrived as naval warfare weapons, but also offers a datapoint suggesting technologies developed by the U.S. Navy to counter the ballistic threat are on the right track.

MOSES'

BIBLICAL PARTING OF THE RED SEA

Conflicts

in this troubled region of Planet Earth are nothing new. In

the Bible, Moses led his people to the Promised Land.

In the Exodus narrative, Yam Suph or Reed Sea, sometimes translated as Sea of Reeds, is the body of water which the Israelites crossed following their exodus from Egypt. The same phrase appears in over 20 other places in the Hebrew Bible. This has traditionally been interpreted as referring to the Red Sea, following the Greek Septuagint's rendering of the phrase. However the appropriate translation of the phrase remains a matter of dispute; as does the exact location referred to.

While the identity of the Pharaoh in the story of Moses is not explicitly stated in

the

Bible, there are strong historical and textual clues that point to Ramses II.

Here's why:

- Timeline: Ramses II's reign (1279-1213 BC) aligns with the estimated timeframe for the Exodus based on other historical and archaeological evidence.

- Building projects: The Bible mentions that the Israelites were enslaved in building cities such as Pithom and Raamses. Archaeological excavations have unearthed evidence of these cities, and inscriptions linking them to Ramses II's reign.

- Egyptian records: While there are no direct references to the Exodus in Egyptian records, some scholars believe certain events, such as natural disasters or plagues, could be connected to the biblical narrative.

While the identity of the Pharaoh in the story of Moses is not explicitly stated in the Bible, there are strong historical and textual clues that point to Ramses II.

It's important to note that the identification of Ramses II as the Pharaoh is not universally accepted. Some scholars propose other candidates, such as Seti I, Ramses I, or even an amalgamation of several

pharaohs over time. However, Ramses II remains the most favored candidate based on the available evidence.

Ultimately, the identity of the Pharaoh remains a subject of historical debate and theological interpretation. But regardless of who the specific ruler was, the story of Moses and the Exodus stands as a powerful testament to faith, freedom, and divine intervention.

WHERE

WAS MOSES HEADING AND WHY?

After escaping

the Pharaoh's wrath in Egypt, Moses' destination and purpose shifted throughout his journey, driven by both divine calling and circumstance. Here's a breakdown of his key movements:

1. Fleeing to Midian:

- Where: Midian, a land east of the Sinai Peninsula, inhabited by nomadic tribes.

- Why: After killing an Egyptian overseer in defense of a Hebrew slave, Moses fled for his life to avoid Pharaoh's death sentence.

2. The Burning Bush and Divine Mission:

- Where: Mount Horeb, located in the Sinai Peninsula.

- Why: While tending his flocks, Moses encountered God in the form of a burning bush and received his divine mission: to lead the Israelites out of Egyptian slavery and back to their promised land in Canaan.

3. Returning to Egypt:

- Where: Egypt, specifically the Pharaoh's court.

- Why: Following God's instructions, Moses returned to Egypt to confront Pharaoh and demand the release of the Israelites. This eventually led to the Ten Plagues and the dramatic parting of the Red Sea, allowing the Israelites to escape.

4. Wandering in the Wilderness:

- Where: The Sinai Desert for 40 years.

- Why: Despite escaping Egypt, the Israelites' journey to Canaan was not straightforward. They wandered in the desert for four decades, facing challenges like food and water shortages, rebellions, and idol worship. During this time,

Moses received the Ten Commandments and established the covenant between God and the Israelites.

This was made into an epic film in 1956, by Cecile B. DeMille,

starring Charlton Heston and Yul Brynner.

5. Approaching the Promised Land:

- Where: The borders of the Canaanite land.

- Why: After years of hardship and lessons learned, the Israelites finally reached the doorstep of the land promised to them by God. However, due to their lack of faith and disobedience, Moses was not permitted to enter. He ascended Mount Nebo and viewed the promised land from afar before passing away.

So, Moses' journey was multifaceted, driven by a combination of escaping persecution, fulfilling a divine calling, guiding his people, and establishing their religious and societal foundations. While he never reached the final destination himself, his leadership and actions paved the way for the Israelites to inherit their promised land.

WHO

WAS MOSES?

Moses is considered the most important prophet in Judaism and one of the most important prophets in

Christianity, Islam, the Druze faith, the Baháʼí Faith, and other Abrahamic religions. According to both the Bible and the Quran, Moses was the leader of the Israelites and lawgiver to whom the authorship, or "acquisition from heaven", of the Torah (the first five books of the Bible) is attributed.

According to the Book of Exodus, Moses was born in a time when his people, the Israelites, an enslaved minority, were increasing in population and, as a result, the Egyptian Pharaoh worried that they might ally themselves with Egypt's enemies. Moses' Hebrew mother, Jochebed, secretly hid him when Pharaoh ordered all newborn Hebrew boys to be killed in order to reduce the population of the Israelites. Through Pharaoh's daughter (identified as Queen Bithia in the Midrash), the child was adopted as a foundling from the Nile and grew up with the Egyptian royal family. After killing an Egyptian slave-master who was beating a Hebrew, Moses fled across the Red Sea to Midian, where he encountered the Angel of the Lord, speaking to him from within a burning bush on Mount Horeb, which he regarded as the Mountain of God.

God sent Moses back to Egypt to demand the release of the Israelites from

slavery. Moses said that he could not speak eloquently, so God allowed Aaron, his elder brother, to become his spokesperson. After the Ten Plagues, Moses led the Exodus of the Israelites out of Egypt and across the Red Sea, after which they based themselves at Mount Sinai, where Moses received the Ten Commandments. After 40 years of wandering in the desert, Moses died on Mount Nebo at the age of 120, within sight of the Promised Land.

Generally, the majority of scholars see the biblical Moses as a legendary figure, whilst retaining the possibility that Moses or a Moses-like figure existed in the 13th century

BCE. Rabbinical Judaism calculated a lifespan of Moses corresponding to 1391–1271 BCE; Jerome suggested 1592

BCE, and James Ussher suggested 1571 BCE as his birth year.

The Egyptian name "Moses" is mentioned in ancient Egyptian literature. In the writing of Jewish historian Josephus, ancient Egyptian historian Manetho is quoted writing of a treasonous ancient Egyptian priest, Osarseph, who renamed himself Moses and led a successful coup against the presiding pharaoh, subsequently ruling Egypt for years until the pharaoh regained power and expelled Osarseph and his supporters.

PARTING

OF THE RED SEA (OF REEDS)

The Crossing of the Red Sea or Parting of the Red Sea is an episode in the origin myth of The Exodus in the Hebrew Bible.

It tells of the escape of the Israelites, led by Moses, from the pursuing Egyptians, as recounted in the Book of Exodus. Moses holds out his staff and God parts the waters of the Yam Suph, which is traditionally presumed to be the Red Sea, although other interpretations have arisen. With the water dispersed, the Israelites were able to walk on dry ground and cross the sea, followed by the Egyptian army. Once the Israelites have safely crossed, Moses drops his staff, closing the sea, and drowning the pursuing Egyptians.

No archaeological, scholar-verified evidence has been found that supports a crossing of the Red Sea. Given the lack of evidence for the biblical account, some have searched for explanations as to what may have inspired the biblical authors' narrative, or to provide a natural explanation.

After the Plagues of Egypt, the Pharaoh agrees to let the Israelites go, and they travel from Ramesses to Succoth and then to Etham on the edge of the desert, led by a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night. There God tells Moses to turn back and camp by the sea at Pi-HaHiroth, between Migdol and the sea, directly opposite Baal-zephon.

God causes the Pharaoh to pursue the Israelites with chariots, and the pharaoh overtakes them at Pi-hahiroth. When the Israelites see the Egyptian army they are afraid, but the pillar of fire and the cloud separates the Israelites and the Egyptians. At God's command, Moses held his Staff out over the water, water parted, and the Israelites walked through on dry land with a wall of water on either side (Exodus 14:21&22). The Egyptians pursued them, but at daybreak God clogged their chariot-wheels and threw them into a panic, and with the return of the water, the pharaoh and his entire army are destroyed. When the Israelites saw the power of God, they put their faith in God and in Moses, and sang a song of praise to the Lord for the crossing of the sea and the destruction of their enemies. (This song, at Exodus 15, is called the Song of the Sea).

The narrative contains at least three and possibly four layers. In the first layer (the oldest), God blows the sea back with a strong east wind, allowing the Israelites to cross on dry land; in the second, Moses stretches out his hand and the waters part in two walls; in the third, God clogs the chariot wheels of the Egyptians and they flee (in this version the Egyptians do not even enter the water); and in the fourth, the Song of the Sea, God casts the Egyptians into tehomot, the oceanic depths or mythical abyss.

ON THE EXODUS STORY

Zahi Hawass, an Egyptian archaeologist and formerly Egypt's Minister of State for Antiquities Affairs, said of the Exodus story, which is the biblical account of the Israelites’ flight from Egypt and subsequent 40 years of wandering the desert in search of the Promised Land: "Really, it’s a myth... Sometimes as archaeologists we have to say that never happened because there is no historical evidence."

Given the lack of evidence for the biblical account, some have searched for explanations as to what may have inspired the biblical authors' narrative, or to provide a natural explanation. One explanation is that the Israelites and Egyptians experienced a mirage, a commonly occurring natural phenomenon in deserts (and mirages themselves may have been considered supernatural). Each group may have believed the other to have been submerged in water, resulting in the Egyptians assuming the Israelites drowned and thus called off the pursuit. Some have claimed that the parting of the Red Sea and the Plagues of Egypt were natural events caused by a single natural disaster, a huge volcanic eruption on the Greek island of Santorini in the 16th century BC. Another proposal is that a land path through the Eastern Nile Delta was created by a wind setdown.

IN ISLAM

The incident of the Egyptian tyrant Pharaoh chasing down Moses and the Israelites, followed by the drowning in the sea, is mentioned in several places in the Quran. As per God's command, Moses came to the court of Pharaoh to warn him for his transgressions. Mūsā clearly manifested the proof of prophethood and claimed to let Israelites go with him. The Magicians of Pharaoh's cities, whom he gathered to prove to the people that the person claiming to be prophet is a magician; eventually they all believed in Moses. This enraged Pharaoh. But he couldn't frighten them in any way. Later they were pursued by Pharaoh and his army at sunrise. But God revealed to Moses beforehand to leave with His servants at night, for they will be pursued. The Quranic account about the moment:

When the two groups came face to face, the companions of Moses cried out, “We are overtaken for sure.” [Moses] said, "No! Indeed, with me is my Lord; He will guide me." So We inspired Moses: “Strike the sea with your staff,” and the sea was split, each part was like a huge mountain.

— Quran 26:61-63

Miraculously, God divided the waters of the sea leaving a dry path in the middle, which the Children of Israel immediately followed. Pharaoh and his soldiers went so audacious as to chase the Children of Israel into the sea. Nevertheless, this miracle did not suffice to convince Pharaoh. Together with his soldiers who took him as a deity (by obeying him against the prophet of God), he blindly entered the path that divided the sea. However, after the Children of Israel had safely crossed to the other side, the waters suddenly began to close in on Pharaoh and his soldiers and they all drowned. Though, at the last moment Pharaoh tried to repent but Jibreel put mud in his mouth and his repentance was not accepted:

We brought the tribe of Israel across the sea and Pharaoh and his troops pursued them out of tyranny and enmity. Then, when he was on the point of drowning, he (Pharaoh) said, "I believe that there is no god but Him in Whom the tribe of Israel believe. I am one of the Muslims (those who submit to God’s will)." What, now! When previously you rebelled and were one of the corrupters? Today We will preserve your body so you can be a Sign for people who come after you. Surely many people are heedless of Our Signs.

— Quran 10:90-92

Every year Muslims fast two days in the month of Muharram commemorating the event.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/pharaoh-king-punished-god

https://www.britannica.com/place/ancient-Egypt/Ramses-II

AEGEAN

- ACIDIFICATION

- ADRIATIC

- AMBRACIAN

GULF

- ARCTIC

- ATLANTIC

- BALTIC

- BAY

BENGAL - BAY

BISCAY - BERING

- BLACK

- CARIBBEAN

- CASPIAN

- CORAL

- EAST

CHINA SEA

ENGLISH

CH - GOC

- GUANABARA

- GULF

GUINEA - GULF

MEXICO - INDIAN

-

IRC - IONIAN - IRISH

- MEDITERRANEAN

- NORTH

SEA - PACIFIC

- PERSIAN

GULF - SEA

JAPAN

STH

CHINA - PLASTIC

- PLANKTON

- PLASTIC

OCEANS - RED

- SARGASSO

- SEA

LEVEL RISE - SOUTHERN - TYRRHENIAN

- UNCLOS

- UNEP

- WOC

- WWF

This

website is provided on a free basis as a public information

service. copyright © Cleaner

Oceans Foundation Ltd (COFL) (Company No: 4674774)

2025 Solar

Studios, BN271RF, United Kingdom.

COFL

is a charity without share capital. The names Amphimax™

and SeaVax™

are trademarks.

|