|

UN

- CLIMATE

CHANGE COP 26 2020

CLIMATE

| ELECTRICITY

| RIGHTS

| HYDROGEN

| PLASTIC

| SPACE

| TRANSPORT

| NATIONS

Please

use our A-Z INDEX

to navigate this site, or HOME

ENERGY

VOICE 8 JANUARY 2020

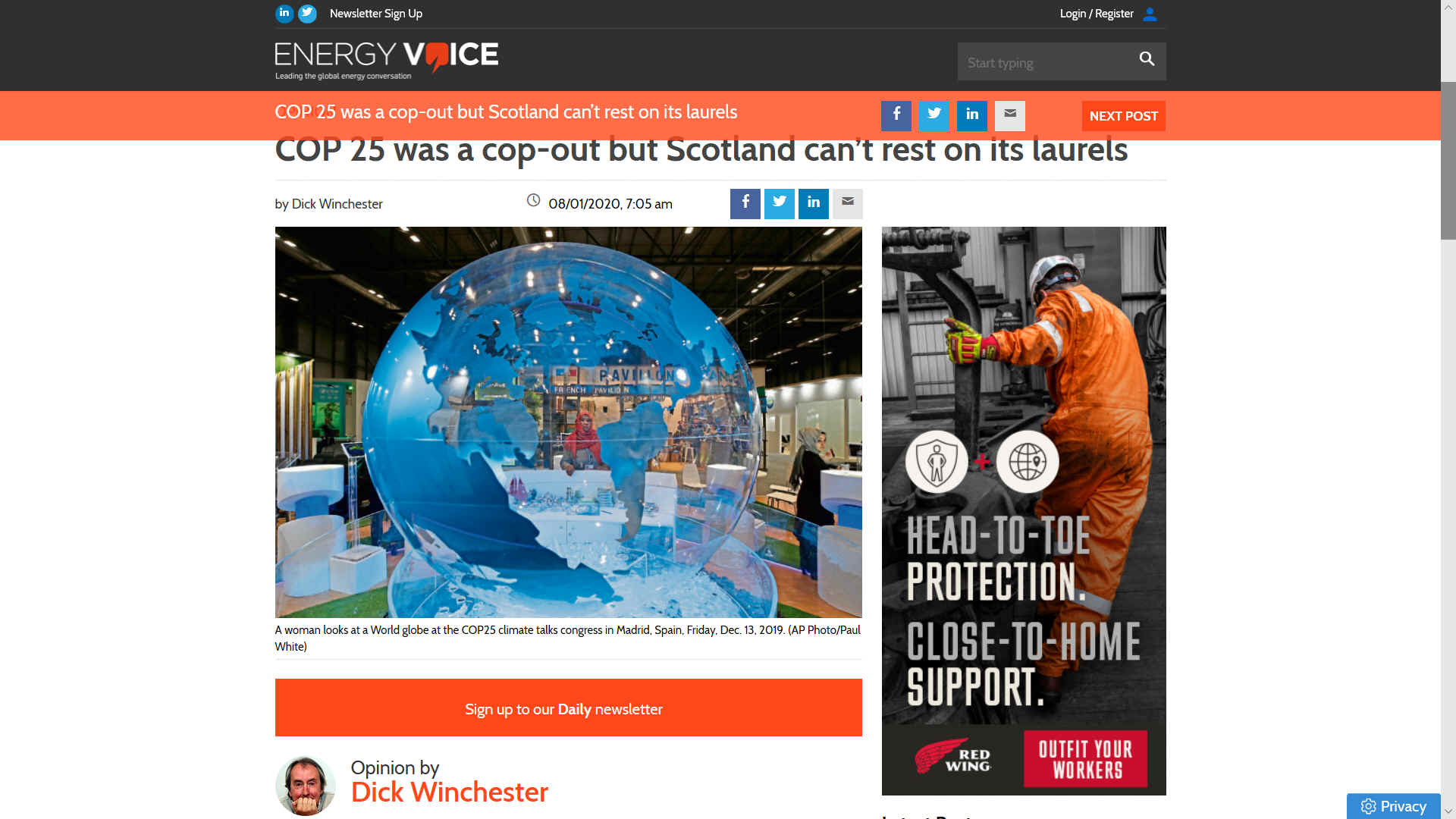

News that the COP 25 meeting in Madrid ended in a not very satisfactory compromise doesn’t exactly fill me with hope that the world’s leaders have really got a grip of how serious the

“climate

emergency” really is.

The US,

Brazil,

India and

China opposed a more ambitious plan on

greenhouse gas reductions. This shouldn’t surprise us. These are nations run by people who take pride in ignoring what everyone else thinks. China’s decision to build even more

coal-fired power stations tells me they’re not interested in being reasonable. Although, they are extremely active in rolling out net-zero technologies

The leader of one of those countries may be history by the time of the next COP, in Glasgow in 2020.

Other questions – including what to do about carbon markets – were delayed until Glasgow.

I am opposed to carbon markets. The idea that one party can pay compensation to another for damaging the planet is risible. There is only one way of dealing with climate change and it’s not playing financial games but applying technology. Financialising climate change may sound like a good idea to the financial community because they will undoubtedly make money, but I wouldn’t trust them to achieve anything positive.

Let’s not get too cocky about how good Scotland is at dealing with climate change. According to the Committee on

Climate Change (CCC), Scotland is at risk of missing its 2020 carbon target of a 56% cut in emissions.

The CCC believes that although emissions fell by 3%, Scotland didn’t meet its annual target for emissions reduction in 2017. That 3% was also a lot less than the 10% fall seen in 2016.

Making policy and setting targets is the easy bit. The difficult bit is delivering on them and it’s especially hard for a devolved government with only limited powers that it can use particularly when it comes to fiscal and other financial levers.

Just before the election it was announced that an Oil and Gas Technology Centre project to test the feasibility of producing

hydrogen offshore on “redundant” oil and gas platforms had not won any further funding from the UK Government, despite a successful initial study.

Given everything going on in Europe on hydrogen production, including a Danish project to construct artificial offshore islands to tie in power from offshore wind and use some of that energy to produce

hydrogen, it just strikes me as naive and obstructive that the UK should decide not to provide further support.

Whilst we prevaricate over whether to spend what are relatively trivial amounts on small demonstration projects, large parts of the rest of the world are rapidly building their net zero capabilities.

The consequences to the slow movers like the UK and Scotland can be economically harmful.

Cummins, the US company renowned for its diesel engines has decided to close its engine factory in Cumbernauld in Scotland, making around 130 people redundant.

Cummins claims the closure is due to market conditions. Companies and others are simply buying less diesel-powered everything and whilst that’s unfortunate for the 130 losing their jobs it’s the right response to climate change.

However, what people also need to know but probably don’t is that Cummins recently bought the Canadian

hydrogen fuel cell and electrolyser company Hydrogenics. That’s the same company that provided the Aberdeen hydrogen bus refueller.

The Cummins plan is to use Hydrogenics’ technology to transition away from diesel to hydrogen and – presumably – eventually use it on all or most of their power applications.

The head scratching around the Holyrood cabinet table should be about why didn’t we have a Hydrogenics of our own, how do we stop the almost inevitable job leakage if we don’t have the companies like Hydrogenics to absorb them and why the heck didn’t we see this coming?

Lord Deben, chair of the CCC, says Scotland’s Net Zero target is “world-leading”, but now the country needed to “walk the talk”.

He’s right. Take a leaf from the Italians’ book. The boss of the SNAM natural gas infrastructure company has proposed setting up an “Airbus of Hydrogen” to drive forward the production and application of hydrogen.

I can see this happening. I can also see us – post Boris Johnson’s Brexit – playing no part in it whatsoever.

By Dick WInchester

THE

G20 @ COP 26, GLASGOW, 2021

|

ARGENTINA

|

AUSTRALIA

|

BRAZIL

|

CANADA

|

CHINA

|

|

EUROPEAN

UNION

|

FRANCE

|

GERMANY

|

INDIA

|

INDONESIA

|

|

ITALY

|

JAPAN

|

MEXICO

|

RUSSIA

|

SAUDI

ARABIA

|

|

SOUTH

AFRICA

|

SOUTH

KOREA

|

TURKEY

|

UNITED

KINGDOM

|

UNITED

STATES

|

AGRICULTURE | BANKS | HOUSING | GROUP20 | INDUSTRY | MONEY | POLITICS | RENEWABLES | TRANSPORT

CLIMATE CHANGE NEWS 19 MARCH 2019

Britain and Italy are squaring off to host the UN’s 2020 climate change summit – a key moment where countries will be expected to ramp up their commitments under the Paris Agreement.

However, both countries face significant domestic uncertainties that year, with the strong possibility of early general elections and economic and political problems.

In the UK, it’s not yet clear if the country will have left the

European Union by then, be in the middle of a transition or even still locked in negotiations over leaving the bloc.

In Italy, current public opinion polls predict a full-out win for the right-wing League party, which now shares power with the populist 5 Star Movement.

“New elections before the Cop26 are important because they can change a government’s priorities,” said Luca Bergamaschi, an energy and climate change expert at the think-tanks E3G and

Italian Institute for International Affairs. “Having a Cop26 potentially guided by the League raises strong doubts about whether Italy could guide a meeting which is very, very important.”

While the UK government may still be consumed by Brexit or its fallout, Britain has “the diplomatic network to pull off the significant outreach that will be required of the Cop26 presidency”, said Jennifer Tollmann, a policy advisor also at E3G. “It has consistently driven the climate agenda within Europe and there are numerous cities that could host it.”

The government has also made an effort to show leadership in recent years. It partnered with Canada in 2017 to form an anti-coal alliance, started the process of strengthening its 2050 climate goals last year, and is now co-chairing talks on climate resilience for a special

UN summit in September.

The annual Cop summits rotate between five regional groups. Britain and Italy sit with other Western European countries, the

US,

Australia,

Canada, Iceland, New Zealand,

Norway and

Switzerland.

Italy first floated the idea of hosting under the previous Democratic Party-led government early last year.

The country’s environment ministry is now run by the 5 Star Movement, which tends to advocate for stronger environmental and climate change measures.

The League has largely stayed out of environmental policy since the coalition government took over a year ago, except in supporting a controversial gas pipeline and other infrastructure projects. However, its European Parliament members – including now-party leader and interior minister Matteo Salvini – voted against ratifying the Paris accord in 2016.

A fight is also brewing over where the summit would be held in

Italy.

The northern region of Lombardy, which includes Milan, wrote a letter to the government asking to be considered, even though environment minister Sergio Costa has mentioned his home city of Naples, the newspaper Il Denaro reported in February. Milan hosted the Cop9 in 2003, and was the Democratic Party’s preferred location.

The regional group is expected to decide on the winner later this year, either at talks in Bonn or at the Cop25 summit in Chile.

By Sara Stefanni

STATEMENT

20 DECEMBER 2018 - UNFCCC - "The

24th conference of the parties (COP24)

to the United Nations framework convention on climate change (UNFCCC)

took place in Katowice, Poland, from 2 to 15 December. I led

the United Kingdom delegation, accompanied by the Minister for

Asia and the Pacific, my right hon. Friend the Member for

Cities of London and Westminster (Mark Field), and the

Under-Secretary of State for Environment, Food

and Rural Affairs, my hon. Friend the Member for Suffolk

Coastal (Dr Coffey). As a demonstration of the UK’s action

at all levels, the First Minister of Scotland and the Scottish

Cabinet Secretary for the Environment also attended, as well

as the Deputy Premier of the Government of the British Virgin

Islands, representing the UK overseas territories.

The UK’s priorities for COP24 were to accelerate the global

political momentum to combat climate change by i) securing a

rulebook that would enable the historic Paris agreement to be

effectively implemented: and ii) engaging in a constructive

dialogue on ambition (the “Talanoa dialogue”) that would

generate confidence and enhance action. In doing so, we were

also determined to promote the UK’s global climate

leadership.

COP24 was an important moment, representing the culmination of

three years of negotiations and following shortly after the

publication of a landmark scientific report from the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate

Change that highlighted the severe consequences of failing

to limit global

warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

In the negotiations we succeeded in securing our main

objectives by delivering an operational rulebook to drive

genuine climate action, creating a level playing field, while

allowing for flexibility and support for those countries that

need it, in light of capacity. Inevitably there is still work

to be done, particularly on carbon markets, but the overall

picture is of a rulebook that enables the Paris agreement to

be taken forward in practice, marking a move from negotiation

to implementation.

The UK championed the latest climate science during COP. We

played a central role in the progressive alliance of countries

striving for a legal outcome that coupled robust rules with a

call for more ambitious climate action—both through

supporting the High Ambition Coalition’s Stepping Up Climate

Ambition statement and through regularly convening the

Cartagena dialogue of progressive countries.

Outside the negotiations, the UK had a visible presence at

COP. We celebrated one year of the powering past coal

alliance (PPCA) that was launched last year. The UK

pavilion had over 50 events showcasing UK international

support, domestic action, and low carbon

expertise. We also made new domestic commitments, including

the announcements of a clean growth grand challenge mission to

establish one net-zero carbon

industrial cluster by 2040 and at least one low carbon cluster

by 2030. To kick-start this mission we will invest up to £170

million to develop and deploy low carbon technologies and

enable infrastructure

in one or more clusters, and we will also provide up to £66

million to develop new technologies and establish innovation

centres to support the transformation of our foundation

industries.

The UK reaffirmed our commitment to supporting climate action,

highlighting recent announcements including an additional £100

million of UK climate finance for the renewable

energy performance platform (REPP) to support 40 renewable

energy projects in sub-Saharan

Africa, as well as £106 million for green construction

and £60 million to build capacity to drive clean growth and

emissions reductions in key developing countries.

We were also pleased to support Poland as COP presidency in

their role, both through constructive engagement on

negotiations and also in their three political declarations. The

Prime Minister, my right hon. Friend the Member for

Maidenhead (Mrs May), signed the declaration on “just

transition”, promoting efforts to ensure no workers or

communities are left behind in the transition towards a low

carbon future. The UK co-developed Poland’s declaration on

e-mobility (building on our successful zero emission vehicle

summit in Birmingham in September), and we also supported

their declaration on forestry.

We now turn our attention to 2019 and beyond, including the UN

Secretary General’s climate summit next September, which

will be a vital step as countries look to raise their ambition

ahead of 2020. COP26 in 2020 will be a pivotal moment to

encourage and take stock of global ambition and prepare the

ground for further action. It is for that reason that the UK

expressed interest in hosting COP26, continuing to show our

global leadership in climate action. However, we note the

interest of other countries and will engage with them on this

matter. Our priority is to ensure that the conference of the

parties is a success."

FINANCIAL TIMES MAY 9 2018 - Britain lobbies for right to host 2020 climate meeting

Conservative government wants to point up its green credentials and draw younger voters

Theresa May’s government is lobbying for the right to host a crucial climate meeting in 2020, in a sign of the prime minister’s determination to highlight the Conservative party’s green credentials.

Claire Perry, the energy minister, said on Wednesday that the UK planned to put its name in the ring for the UN’s main annual climate change conference in 2020.

“I think it would be a marvelous opportunity for the UK to host it,” she said, in the first public indication of the UK’s interest in hosting the high-profile gathering.

The UN’s yearly climate change conference sits at the heart of the diplomatic and political negotiations around implementing the global climate change accord agreed in Paris in 2015.

The host country for the 2020 conference will not be formally selected until next year, but several countries, including Italy and Turkey, have already expressed an informal interest, according to the UN organisers.

“2020 will be extremely significant for a lot of reasons, because that is when the Paris agreement becomes operational, so we expect a lot of interest from countries in hosting,” said Ovais Sarmad, deputy executive secretary at the UN climate change secretariat in Bonn.

The annual meeting rotates between five global regions, with the 2020 meeting due to take place in western Europe. The host is selected through a consultation process within the regional bloc.

In the past, countries have not always been eager to host the conference, in part because of the steep cost of organising logistics for tens of thousands of delegates and security for visiting heads of state.

Mr Sarmad estimated that the typical conference might cost between €100m to €120m to organise, although the costs are shared between the host and other member countries.

Ms Perry said that there were still “diplomatic questions” surrounding a potential UK bid, but added that hosting the climate conference was “being discussed already in the government”.

She pointed to the UK’s recent legislation on climate change — which includes introducing mandatory carbon targets and a commitment to close all coal power stations by 2025— as evidence of the government’s commitment to the issue.

“We absolutely lead this space. We’ve decarbonised more and grown more than any other G7 country,” she said. “I’ve got a fantastic team of climate negotiators in the department. Our word carries weight, and it will still be so after Brexit.”

The host of the UN climate meeting also plays an important political role in the conference’s outcome. A host country must appoint a president for the meeting with the job of mobilising political support across the member countries ahead of the conference.

The UK government has accelerated its green agenda since a poll conducted for the Tories last year found that climate change was the issue voters between the ages of 18 and 28 wanted politicians to prioritise more.

By Leslie Hook and Laura Hughes

THE GUARDIAN DECEMBER 13 2018

- UK bids to host 2020 UN climate change summit

Chile and Costa Rica thought to be considering alternative bids after Brazil withdrew offer.

Britain is bidding to host the UN climate change conference in 2020, the biggest since the Paris agreement was signed in 2015, as part of the government’s aim to be seen as a green leader.

The conference will mark a vital deadline for countries to comply with their commitments on reducing greenhouse gas emissions and move on to tougher targets for the decade to 2030, and so it is likely to be a fractious affair.

If successful, the move would be a strong signal of the UK government’s determination to retain its role on the world stage after Brexit.

Claire Perry, the climate change minister, flew to Poland on Thursday after taking part in the Conservative party’s vote on Theresa May’s future, which she called “24 hours of political self-indulgence”.

Perry told journalists: “We have to make sure we can deliver a good COP [Conference of the Parties], as 2020 will be a really vital COP, and we absolutely want to be part of that process [of making it a success].”

She pointed to the UK’s efforts in cutting greenhouse gas emissions and investing in green jobs, saying Britain had decarbonised faster per unit of GDP than any other country in the past decade, and created 400,000 jobs in the low-carbon economy. “We have a really good track record in the UK,” she said.

In Poland, the UK joined with other EU member states and scores of developing countries in committing to scale up their ambition on climate change, with a focus on preventing global warming from breaching 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, in line with scientific warnings.

The UN awards the hosting of the COP, as the annual meeting is known, usually by alternating among developed and developing countries, and different continents, though the rules can be somewhat flexible. Next year’s host was supposed to be Brazil, but the incoming president, Jair Bolsonaro, is hostile to the Paris agreement and has withdrawn the offer. Chile and Costa Rica are understood to be considering alternative bids.

Some campaigners at the current climate change talks in Poland, which have stalled over continuing disagreements on how to implement the Paris agreement, praised the UK’s move.

Gareth Redmond-King, the head of climate change at WWF UK, said: “This is great news and we welcome the bid to host the 2020 [conference]. It’s an opportunity for the UK to lead the way on climate change at a time when the need for action has never been starker.”

COP26, as the 2020 conference is known in UN jargon, will also be notable for the role of the US. Under Donald Trump’s presidency, the country has begun the process of withdrawal from the Paris agreement, but that could be halted if he is replaced in the 2020 election.

Bolsonaro has indicated he may take Brazil out of the Paris agreement, and the divisions between developed and developing countries that have characterised the current talks are likely to remain in the intervening years, giving the UK a diplomatic mountain to climb to make a success of the talks if awarded host-country status.

By Fiona Harvey

1995 COP

1,

BERLIN, GERMANY

1996 COP

2, GENEVA, SWITZERLAND

1997 COP

3, KYOTO, JAPAN

1998 COP

4, BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA

1999 COP

5, BONN, GERMANY

2000:COP

6, THE HAGUE, NETHERLANDS

2001 COP

7, MARRAKECH, MOROCCO

2002 COP

8, NEW DELHI, INDIA

2003 COP

9, MILAN, ITALY

2004 COP

10, BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA

2005 COP

11/CMP 1, MONTREAL, CANADA

2006 COP

12/CMP 2, NAIROBI, KENYA

2007 COP

13/CMP 3, BALI, INDONESIA

2008 COP

14/CMP 4, POZNAN, POLAND

2009

COP 15/CMP 5, COPENHAGEN, DENMARK

2010 COP

16/CMP 6, CANCUN, MEXICO

2011 COP

17/CMP 7, DURBAN, SOUTH AFRICA

2012 COP

18/CMP 8, DOHA, QATAR

2013 COP

19/CMP 9, WARSAW, POLAND

2014 COP

20/CMP 10, LIMA, PERU

2015 COP

21/CMP 11, Paris, France

2016 COP

22/CMP 12/CMA 1, Marrakech, Morocco

2017 COP

23/CMP 13/CMA 2, Bonn, Germany

2018 COP

24/CMP 14/CMA 3, Katowice, Poland

2019 COP

25/CMP 15/CMA 4, Santiago, Chile

2020

COP 26/CMP 16/ CMA 5, Glasgow, Scotland

2021

COP 26/Glasgow, Scotland

2022

CP27/ Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt

UNITED

KINGDOM

UN

CLIMATE ACTION PORTFOLIOS

1.

Finance

2. Energy

Transition

3. Industry

Transition

4. Nature-Based

Solutions

5. Cities

and Local Action

6. Resilience

and Adaptation

7. Mitigation

Strategy

8. Youth

Engagement & Public Mobilization

9. Social

and Political Drivers

DESERTIFICATION

COP HISTORY

|

COP

1:

Rome, Italy, 29 Sept to 10 Oct 1997

|

COP

9: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 21 Sept to 2 Oct

2009

|

|

COP

2: Dakar, Senegal, 30 Nov to 11 Dec 1998

|

COP

10: Changwon, South Korea, 10 to 20 Oct 2011

|

|

COP

3: Recife, Brazil, 15 to 26 Nov 1999

|

COP

11: Windhoek, Namibia, 16 to 27 Sept 2013

|

|

COP

4: Bonn, Germany, 11 to 22 Dec 2000

|

COP

12: Ankara, Turkey, 12 to 23 Oct 2015

|

|

COP

5: Geneva, Switzerland, 1 to 12 Oct 2001

|

COP

13: Ordos City, China, 6 to 16 Sept 2017

|

|

COP

6: Havana, Cuba, 25 August to 5 Sept 2003

|

COP

14: New Delhi, India, 2 to 13 Sept 2019

|

|

COP

7: Nairobi, Kenya, 17 to 28 Oct 2005

|

COP

15: 2020

|

|

COP

8: Madrid, Spain, 3 to 14 Sept 2007

|

COP

16: 2021

|

BIODIVERSITY

COP HISTORY

|

COP

1:

1994 Nassau, Bahamas, Nov & Dec

|

COP

8: 2006 Curitiba, Brazil, 8 Mar

|

|

COP

2: 1995 Jakarta, Indonesia, Nov

|

COP

9: 2008 Bonn, Germany, May

|

|

COP

3: 1996 Buenos Aires, Argentina, Nov

|

COP

10: 2010 Nagoya, Japan, Oct

|

|

COP

4: 1998 Bratislava, Slovakia, May

|

COP

11: 2012 Hyderabad, India

|

|

EXCOP:

1999 Cartagena, Colombia, Feb

|

COP

12: 2014 Pyeongchang, Republic of Korea, Oct

|

|

COP

5: 2000 Nairobi, Kenya, May

|

COP

13: 2016 Cancun, Mexico, 2 to 17 Dec

|

|

COP

6: 2002 The Hague, Netherlands, April

|

COP

14: 2018 Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, 17 to 29

Nov

|

|

COP

7: 2004 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Feb

|

COP

15: 2020 Kunming, Yunnan, China

|

CONTACTS

The

UNFCCC secretariat is located at two different locations.

Main

office

UNFCCC secretariat

UN Campus

Platz der Vereinten Nationen 1

53113 Bonn

Germany

Haus Carstanjen Office

Martin-Luther-King-Strasse 8

53175 Bonn

Germany

Mailing address

UNFCCC secretariat

P.O. Box 260124

D-53153 Bonn

Germany

Phone: (49-228) 815-1000

Fax: (49-228) 815-1999

Web: http://unfccc.int

info@climateactionprogramme.org

http://www.climateactionprogramme.org

LINKS

& REFERENCE

https://www.energyvoice.com/opinion/215362/cop-25-was-a-cop-out-but-scotland-cant-rest-on-its-laurels/

http://www.ukpol.co.uk/claire-perry-2018-statement-on-unfccc-conference-of-parties/

https://theecologist.org/2019/mar/20/uk-and-italy-bid-2020-climate-talks

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/dec/13/uk-bids-to-host-2020-un-climate-change-summit

https://www.climatechangenews.com/2019/03/19/uk-italy-bid-2020-climate-talks-amid-political-uncertainty/

https://www.ft.com/content/da9bb032-5391-11e8-b3ee-41e0209208ec

COP

THAT - The United Nations Climate Change Conferences are yearly conferences held in the framework of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

(UNFCCC). They serve as the formal meeting of the UNFCCC Parties (Conference of the Parties, COP) to assess progress in dealing with climate change, and beginning in the mid-1990s, to negotiate the Kyoto Protocol to establish legally binding obligations for developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. From 2005 the Conferences have also served as the "Conference of the Parties Serving as the Meeting of Parties to the

Kyoto

Protocol" (CMP); also parties to the Convention that are not parties to the Protocol can participate in Protocol-related meetings as observers. From 2011 the meetings have also been used to negotiate the

Paris Agreement as part of the Durban platform activities until its conclusion in 2015, which created a general path towards climate action. The first UN Climate Change Conference was held in 1995 in Berlin.

ABOUT -

CONTACTS - CIRCUMNAVIGATION

- DONATE

- FOUNDATION -

HOME - A-Z INDEX

This

website is provided on a free basis as a public information

service. copyright © Cleaner

Oceans Foundation Ltd (COFL) (Company No: 4674774)

2021. Solar

Studios, BN271RF, United Kingdom.

COFL

is a charity without share capital. The names AmphiMax™,

RiverVax™

and SeaVax™

are trade names used under license by COF in connection with their 'Feed

The World' ocean cleaning sustainability campaign.

|